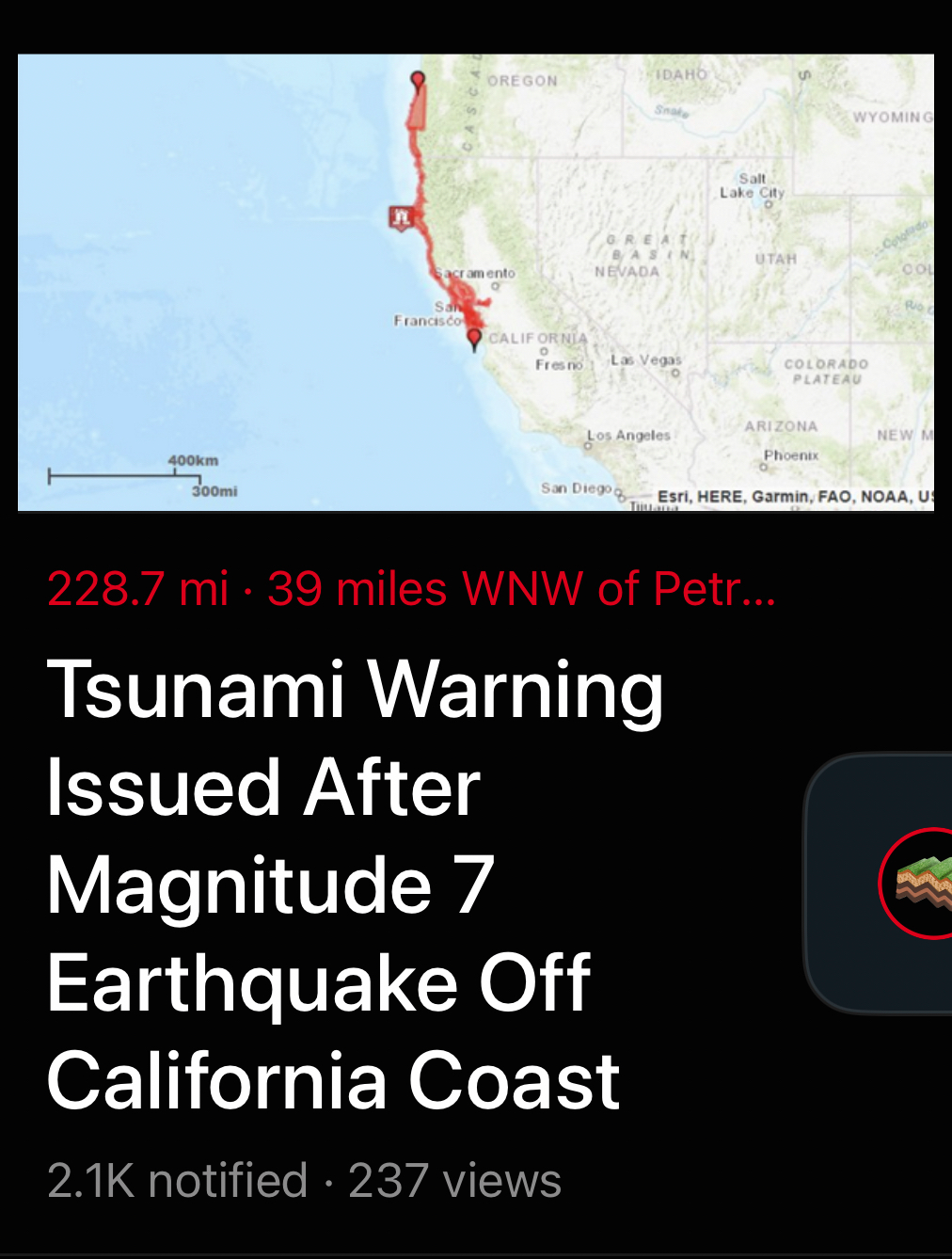

On Dec. 5, Northern California was rocked by a 7.0 magnitude earthquake off the coast of Humboldt County, prompting tsunami warnings to be issued throughout the northern coast of the state, including San Francisco.

Although the quake, being of marginally greater magnitude than the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake, was the strongest recorded in Northern California in nearly 20 years, property damage appears to be relatively minimal, and no casualties have been reported.

Even still, roughly 10 percent of Humboldt County was estimated to be left without power, and moderate damage was incurred in the immediate area through gas leaks, cracked roads, and shifted home foundations.

It is also worth noting that earthquakes of magnitudes above 6.0 have occurred in the same region in 2020, 2021, and 2022, to far less fanfare.

What sets apart this quake–known as the 2024 CapeMendocino Earthquake–is the scale of its response, as tsunami warnings were put in place from southern Oregon to Santa Cruz.

These warnings were received by a projected 5.3 million people, rather tactfully stating “You are in danger” and urging residents to seek higher ground.

This subsequently resulted in small-scale evacuations of select beaches and schools in San Francisco and Pacifica, and both BART’s Transbay Tube and the San Francisco Zoo halted operations.

Arman Mander ’25 expressed that he “was very frightened” but applauded school faculty’s role in quickly elucidating the situation, while Ian Gryb ’25 stated he was “happy it was a false alarm,” and that he feared his home may have been at risk of flooding.

Confusingly, not all apparently applicable citizens received the warning, and warnings appear to have gone off at different times for some individuals, which may have been attributable to different cell providers.

Collectively, this has caused many to question the necessity of the tsunami warning given the almost intrusively widespread nature of the alerts for seemingly no consequence.

Science Instructor and Director of Professional Development Michael O’Brien noted that while the alerts “may have erred on the side of caution” and “spread wide-reaching information to people very unlikely to be affected,” it is ultimately more beneficial to “cast a wide net” when informing the public on matters that could immediately affect their lives and livelihoods.

O’Brien also cited extensive damage and flooding in Santa Cruz harbor due to tsunamis from the 2021 Hunga eruption in Tonga–located over 5,000 miles from the Bay Area–as an example of the threat tsunamis could feasibly present to the Bay Area.

Of critical relevance is that the November earthquake occurred at what is known as the Mendocino Triple Junction, where the boundaries of three plates rendezvous along the San Andreas Fault, Mendocino Fracture Zone, and Cascadia subduction zone. Of these, subduction zones are known to produce tsunamis with their violent vertical motion.

And while the Cape Mendocino Earthquake was eventually concluded to be a product of a strike-slip fault, its proximity to a subduction zone may have been the root of initial alarm and ambiguity as to ascertaining the tsunami risk in the quake’s immediate aftermath.

So while no tsunamis ultimately did occur, the fears placed towards their potential risk weren’t necessarily unfounded. This is all to say that in the aftermath of events such as major earthquakes, details are often lacking or unclear, and false positives would seem to be vastly preferable to the potentially more grim alternative.